NZ Initiative doesn't understand why people don't trust business or the wealthy

A new op-ed urges us to move beyond grievance politics by... doubling down on grievance politics

We haven’t heard much from the NZ Initiative lately. I’ve been looking through their media releases but nothing has really caught my attention. It seems that after the PR surge about the Regulatory Standards Bill and the new report on privatisation, they’ve been relaxing a bit on the more high-profile stuff and focusing on some more esoteric things. Well, I guess there was Bryce Wilkinson’s “come to Jesus” moment. No, he didn’t realize that rich people should take care of the poor, if that’s what you’re thinking. He realized that the Bible could be interpreted to support his regulatory agenda and gave a talk about it at a church where he was participating in a panel discussion.

But a recent op-ed by NZ Initiative’s chairman and senior research member Roger Partridge caught my eye. We haven’t met Partridge before. In addition to co-founding the NZ Initiative, he spent 23 years working at corporate law firm Bell Gully, seven of those as the executive chairman. He is a member of a number of professional societies, including the Mont Pelerin Society, the birthplace of the neoliberal political movement.

Partridge wrote an op-ed in the NZ Herald entitled “Beyond grievance politics: New Zealand’s search for common ground.” The piece is paywalled but NZ Initiative have included it in full on their website here, something they do when they feel that someone has written something really worthwhile that deserves a wider hearing.

And let me tell you, this thing is special. Partridge begins

Trust in New Zealand is fracturing before our eyes. The 2025 Acumen Edelman Trust Barometer reveals a society divided by mistrust.

Partridge is referring to the annual report put out by the Edelman Trust Institute. The full global report can be accessed here while the New Zealand summary can be found here. The report does in fact show a decrease across the board in trust of government, ngos, business, and the media.

Partridge laments that “for the first time, New Zealand’s trust index has fallen below the global average, dropping to 47% compared with the global index of 56%.” While business is the most trusted institution in Aotearoa, with a majority of people rating it as both competent and ethical, it was also the institution that suffered the largest drop in trust, a drop of 6 points from 2024. One gets the feeling that this drop in business trust is particularly distressing to Partridge and the NZI.

Most troubling, mild scepticism about institutions has deepened into widespread grievance. Today, 67% of New Zealanders report moderate to high levels of grievance against government, business, and the wealthy – believing they actively disadvantage ordinary people.

This grievance poisons our collective well-being. Those with high grievance are twice as likely to view society as zero-sum, believing that others’ gains must come at their expense. They also show dramatically lower trust in all institutions. Media trust drops from 45% among those with low grievance to just 25% for those with high grievance. Business trust plummets from 70% to 35%.

67% of New Zealanders report moderate to high levels of grievance against government, business, and the wealthy. That’s a lot. Fully 26% of those surveyed expressed a high level of grievance. This would seem to point to something wrong with the situation here in New Zealand. Perhaps it might be worth exploring why people feel such grievance?

Rather than looking for the source of the grievance in something material or tangible, Partridge dismisses it out of hand as the result of the erosion in institutional trust. The grievance itself is the problem. It does not represent anything valid, but is instead the result of people who don’t have good information and choose instead to politicise everything.

This cycle of grievance and eroding trust has profound consequences. Political discussions revolve around grievances rather than solutions. Without trusted sources of shared facts, New Zealanders retreat to echo chambers.

Evidence of polarisation appears everywhere. On university campuses, legitimate debate suffers. In news media, complex issues get simplistic coverage. Many feel the media has become politicised.

Here we start to get an inkling of where Partridge is going with his piece. If we can’t trust the media, we all just retreat to our echo chambers and so can’t agree on anything. This means that we will just become more polarized. And this means that certain viewpoints are not allowed to be aired in public, according to Partridge. This leads to a lack of legitimate debate and a lack of nuanced coverage of complex issues.

Without him giving any examples, I have a hard time picking out exactly what he’s talking about, but it sure sounds to me like he’s complaining about a censorship of right wing talking points. Again, hard to say for sure, but that’s the vibe I’m getting.

Partridge continues by stating that the Labour government’s Public Interest Journalism Fund decreased trust in media as well

The previous government’s $55 million Public Interest Journalism Fund included politically contentious conditions. Publishers like NZME secured clauses protecting editorial independence. But the PIJF nevertheless created a widespread impression that media organisations had compromised their independence. Meanwhile, media self-censorship has pushed many voices to the margins.

There is it again. I don’t know much about the PIJF, but I know that certain right wing groups and some politicians went hard after it, claiming that it was a bribe by the government to write favourable stories about them, with the Taxpayer’s Union even publishing a list of every media organization that received money from the fund. No word here from Partridge or the NZ Initiative on the proposed takeover of NZME by Canadian billionaire (or multimillionaire, it’s unclear) Jim Grenon. You’d think that would be something they might be concerned about given their classical liberal democratic sensibilities, but they haven’t bothered to cover or comment on it at all.

And that last line about self-censorship pushing many voices to the margins. What kind of voices Roger? Again, this seems like coded language of the sort used by right wing pundits and talking heads when they complain about how their viewpoints are not given equal time on the air. So what types of voices are you talking about Roger? Care to elaborate?

Fortunately we don’t have to wait long before Partridge dives headfirst into uncoded right wing talking points. He rightly blames the issues with inflation for creating a distrust of government economic management. But he also claims that “COVID bred deep scepticism about official information.”

Again I ask, bred deep scepticism from whom? Not the general population, who awarded Ardern’s Labour with a supermajority based on their trust of her Government’s response to the COVID crisis. There were always those who distrusted her, mostly because she was a woman and displayed some emotion and caring, rather than the “wealthy and sorted” vibe that the current Government gives off. And yeah, there was that whole period where a bunch of disgruntled reactionaries, many of whom were racist, misogynist, and bigoted, went and occupied the field in front of the Beehive and set some stuff on fire. Is this the deep scepticism that you’re referring to Roger?

Treaty politics doubtless play a part too, shifting from addressing historical wrongs to competing visions of governance. ACT’s Treaty Principles Bill highlights this tension – a symptom of our focus on reinterpreting the past rather than building our shared future. Each approach pulls us from the pragmatic problem-solving that once defined our politics.

Here is where I think he really gives it away. Oh, I see, Seymour’s bill highlights a tension where some of us want to reinterpret the past rather than building a shared future. So I’m assuming that the ones who want to reinterpret the past are those who are against Seymour’s bill, and those who just want to get on with building a shared future already are the ones for the bill? Why can’t we just focus on a pragmatic problem-solving strategy like we used to without letting a history of colonialism and entrenched systemic injustice and inequality get in the way? People really can’t see the full picture, can they?

Next he tackles the sense of grievance against business and the wealthy. He’s already informed us that people who have a grievance against business and the wealthy feel that they actively disadvantage the rest of us. Well, this is patently absurd for Partridge, because such zero-sum thinking is clearly delusional, as it reflects a paradoxical belief that the rich keep getting richer while the rest of us struggle to keep up

A paradox also shapes our national conversation. Growing economic grievance coincides with stable or declining income inequality. Treasury’s 2024 analysis confirms this trend. Income inequality decreased between 2007 and 2023. Yet perceptions of unfairness keep growing. This disconnect shows how narrative increasingly overpowers reality.

Ah, yes. That pesky inequality narrative. It just won’t go away. And it’s strange, because the Treasury report very clearly shows exactly what Partridge says. That overall, a number of indices of income inequality have decreased since 2007, indicating that contrary to popular belief, wealth inequality is not a problem that we should be concerned with. Certainly not something that should impact our trust in business or the wealthy. Or a sense of grievance, perhaps?

Let’s dig into this report, because it represents a truly disingenuous take by Partridge here. I’d say it’s the closest he comes to actually being dishonest in the piece. He does give the bare facts, but he fails to, as he accused the media of doing above, give anything more than a simplistic treatment.

The Treasury report entitled “Exploring trends in income inequality in New Zealand (2007-2023)” can be found here. In the Key Insights blurb, it says

This report investigates changes to income inequality in New Zealand over the period from 2007 to 2023. We find that income inequality increased to approximately 2013, and then declined, with lower inequality at the end of the period than at the start.

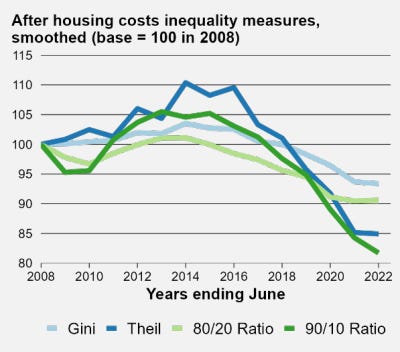

So this accords with Partridge’s summary of the report. The main results can be found in the first figure

Using the year 2007 as the standard, income inequality increased until around 2013 and then decreases. In fact, it appears that for all measures income inequality was lower after 2022 than in 2007.

According to Partridge, then, none of us have anything to worry about, as the wealth inequality we’ve all been worried about is quite literally a figment of our imagination. It is just a case of “narrative increasingly overpower[ing] reality.”

But hold on a minute. The report very clearly states that it is only measuring income inequality. Using income inequality will always give a much more favourable picture because the difference in income will always be less extreme than the difference in overall wealth. This is because a large portion of the wealth of the most wealthy does not come through income. It comes from other sources, such as capital gains and other returns on investments. The report states that its measures of income “do not include income that is not taxed or realised, meaning some returns from capital are not included.” Right away then, we are not dealing with a full picture of wealth inequality.

But it gets worse. Because usual measures of income inequality do not take into account how people spend their money. Poorer people spend much more of their money on living expenses, leaving them with much less disposable income. The Treasury report calculates measures of income inequality both before, and after household costs, as shown below

What is immediately apparent here is that the measure of income inequality is drastically higher after housing costs are subtracted. In fact, the trendline for inequality (blue line) is six points higher after subtracting housing costs than before. This means that the measure of income inequality after subtracting housing costs is three times higher than the total reduction in income inequality before housing costs that occurred over the entire measured period (from 2007 to 2022).1 It’s difficult to argue based on these data for a meaningful reduction in income inequality.

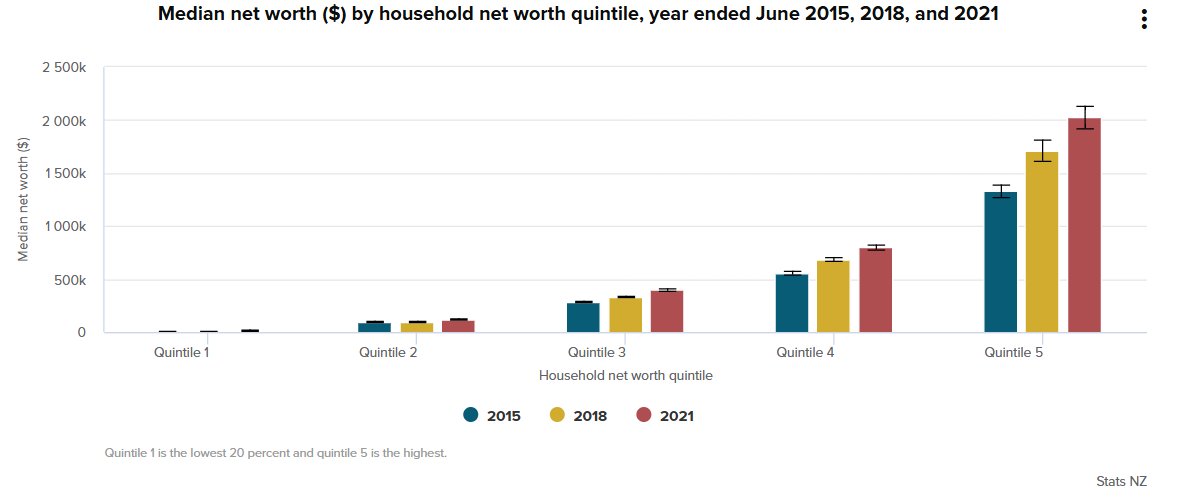

Measures of wealth inequality get us a bit closer to understanding why some people may have a grievance against the wealthy. A 2022 report by Stats NZ broke down the amount of wealth that is owned by New Zealanders. The data are shown below.

What we can see from these data is that the distribution of wealth has not changed meaningfully since 2015. What we can also see is that the top 10 percent of the country own fully 50% of the wealth.

Focusing in on the total value of the wealth owned, rather than simply the distribution, indicates that the rich just keep getting richer, despite the conclusion offered by Partridge.

As summarized by Stats NZ

Although the distribution of wealth has remained unchanged since Stats NZ began its net worth survey in the year ended June 2015, wealthy households continue to see greater increases in the value of their wealth. While the median net worth of the wealthiest 20 percent of New Zealand households (quintile 5) increased by $313,000 in the last three years to $2.02 million for the year ended June 2021, median net worth of the bottom 20 percent of households (quintile 1) increased by $3,000 during the same period to $11,000. That the wealthiest 20 percent of the surveyed households hold 69 percent of total household net worth reflects the uneven distribution of wealth in the country.

Furthermore, those in the lowest 20% own only 1% of assets but 11% of liabilities (debts). All these data, plus the fact that the wealthy in New Zealand pay some of the lowest tax in the OECD, at roughly half what those who are less well-off pay, and the fact that inflation is high at the same time as companies are showing record profits, indicate that there may be something material that is driving the growing sense of grievance towards the wealthy. It is not, as Partridge diagnoses, the result of a fanciful or revolutionary narrative divorced from reality.

Next Partridge singles out the war on ideas

Intellectual conformity adds another layer to our trust crisis. Those questioning the prevailing consensus on social issues face professional consequences. Academic freedom faces constraints and public servants self-censor to avoid repercussions.

Intellectual conformity prevents open debate. Without policy alternatives, ideologically driven approaches prevail over evidence-based ones, eroding accountability and trust.

Here he seems to quite clearly plant his flag in the right wing “free speech” camp. Those questioning the prevailing consensus. Self censoring. Ideologically driven policy approaches as opposed to evidence-based ones. This basically sounds a lot like ACTs newsletter as well as any number of complaints from the right wing commentariat over the past few years about how their ideas never seem to get a fair hearing (these same people will tout the superiority of the free market of ideas, not realizing that if no one wants to hear your ideas, that is the market working). And it is ironic in the extreme that he refers to ideologically driven as opposed to evidence-based policies when as far as I can tell, the current Government has not based any of its policies on any substantive evidence whatsoever.

Partridge is really hitting his groove here

The 2023 election reflected this broader trust crisis, with voters seeking alternatives to status quo views on economic management, social policy, and governance.

Some commentators dismiss these shifts, simplistically blaming either “the rich” or racism. These oversimplifications miss deeper concerns. Many voters worry about fragmentation, seeing grievance-driven politics dividing society into competing groups.

As a nation, we must escape these cycles of grievance and counter-grievance. New Zealanders should remember our shared prosperity came from cooperation and problem-solving. Solutions to our challenges require evidence-based policies, not competing narratives of victimhood.

Fragmentation drains our national energy when we face serious challenges. Housing shortages, declining education standards, healthcare problems, and stagnant productivity demand attention. Instead of uniting around solutions, we waste energy on zero-sum battles

There is a lot to unpack here. First, I’ll agree that the 2023 election reflected this broader trust crisis. What Partridge fails to highlight is that this “trust crisis” was in large part manufactured by the Right during Ardern’s time in office. The COVID pandemic provided the perfect cover for the more reactionary and racist elements in society to band together under a common conspiracy theorist mindset, amplifying these conspiracies, doubling down on right wing rhetoric, and greatly increasing societal fracturing. The three arms of the current coalition Government campaigned on a dog-whistling campaign of racism framed as “law and order” or “equal rights” stoking the fire of groups like Groundswell, Hobson’s Pledge, and others with their attacks on co-governance. Attacks by these groups, along with the newly flush with cash Free Speech Union, I would argue, are the single most significant factor in the fracturing of society along political and ideological lines. These groups import American style media and strategies to create scapegoats along racist, misogynist, and bigoted lines, laying the ground for right wing groups and parties to make significant political inroads.

Partridge seems unwilling to concede these points, or is actively trying to couch his agenda in more palatable language of shared prosperity and problem solving. Nevermind that all of the issues that he highlights—housing shortages, declining education standards, healthcare problems, and stagnant productivity—have not improved or actively gotten worse under the Coalition government, who seem to think that gutting budgets will magically unleash economic prosperity. For Partridge though, decreasing trust in government, business, and the wealthy couldn’t have anything to do with the fact that the Coalition government has cut public services to the bone while somehow finding the money for 14 billion in tax cuts that disproportionately benefitted the wealthy, landlords, and tobacco companies. Don’t worry though, the Government is still considering a corporate tax cut for this year. Their policy agenda is one handout to the rich after another and Partridge can’t see how that would decrease public trust or how continually transferring wealth upwards and building a society based on manufactured scarcity actually does set up a zero-sum game between everyone else.

Luckily, Partridge has some pointers for us to chart a path forward

First, focus on addressing genuine need based on actual circumstances. Avoid group identity or ideology. Housing affordability and educational disadvantage affect people of all backgrounds.

Second, protect robust debate. Avoid accusations against those who question orthodoxy. Different perspectives strengthen our conversation, if they respect evidence and dignity.

Third, build unity around shared civic values. New Zealand’s future depends on working toward common goals despite our diverse backgrounds. While there may be much we disagree on, we can surely find common ground in values like gender and racial equality, freedom of religion and expression, respect for democratic processes and the rule of law.

Fourth, uphold core liberal democratic principles within our unique historical context. Equality before the law and freedom to pursue economic opportunity have created prosperous societies worldwide. These enduring values should guide our approach to addressing today's challenges.

Fifth, adopt a mature approach to Treaty issues that balances aspirations for Māori self-determination with equal political rights for all voters. Granting Māori communities meaningful control over resources and services that directly affect them is important. This should not compromise national governance, which requires democratic accountability to all New Zealanders.

On the face of it, I have no problems with these points. But in today’s current political climate, where “polite” political language is often coded to convey libertarian values for the purpose of enriching the wealthy and corporations, I take issue with some of the his phrasing here. And I don’t think he is any dummy either, and so I don’t think his use of these terms here at the end or throughout is accidental.

His first point of focusing on needs as opposed to group identity could have been written by ACT or Simeon Brown. These are people who will tell you that we need to forget about special treatment based on race and just focus on the need. It’s a coded way of denying the historical and systemic factors which lead to more need in certain racial groups. Rather than address these factors directly, we should just forget about them.

Avoid accusations against those who question orthodoxy. Again, this just sounds like a plea to let people saying racist stuff alone please. Let’s just fan the flames of the racist co-governance talk. Let’s give the Treaty Bill people who want to redefine the treaty a fair hearing. Can’t we all just agree to let people talk even if we disagree? Let’s give the Brian Tamakis the biggest platforms they can get to spread their hate. For some reason, it’s always those on the Left who are accused of breaching the dignity standard, regardless of how flatly ideological and anti-democratic much of what ACT and their supporters and other right wing groups advocate for is and how much they actively fan the flames of persecution for politicians on the Left. It’s okay though, cause most of the time they are talking about selling your country to corporations in nice, dignified, measured tones. We should respect our differences of opinion.

I don’t have a lot of patience for those espousing liberal democratic principles these days. These have all been co-opted by libertarian right wing interests. Equality before the law refers to equality before the market. The market decides winners and losers, and the government does not interfere with its edicts. Equality before the law also means that nothing historically which influences how equal before the law in reality certain people are can be taken into account. We must all just apply the same legal standard to each individual, in the moment, without consideration of any mitigating factors, certainly not something so crass as race. What I hear when Partridge says this is that he wants to guarantee the maximal rights and privileges of the wealthy and corporations, and the rest of us can just go pound sand if our rights and privileges get in the way.

The last point is just a racist apologist strategy for dismantling Treaty protections for Māori. You can couch it in whatever terms you want to, but the fact of the matter is that those who cry the loudest about Treaty protections have the most to gain from dismantling those protections. Property developers and extractive corporations have been stymied for years from coming in and running roughshod over Aotearoa, and it’s the Treaty protections that are holding them at bay. This is why ACT and others are hell bent on dismantling any of these protections.

Sorry Roger, your careful language can’t hide the fact that your organization represents many businesses and corporations that would like nothing better than to see the Treaty dismantled and the law to focus exclusively on property rights and for representation of Māori in governing bodies to be eliminated under the guise of equal voting rights.

Partridge offers this closing statement

This approach does not ignore legitimate grievances. It means treating them as practical problems needing practical solutions, not fuel for identity-based division or class resentment.

Ultimately, rebuilding the fractured trust identified in the Acumen Edelman Trust Barometer requires moving beyond grievance politics. By focusing on evidence-based solutions rather than competing narratives, we can restore the shared facts and pragmatic approach that once defined our politics.

Throughout the piece, Partridge has set up any talk of grievances as an issue with the fracturing of society and the lack of trust in government, media, and business. What then, constitutes a legitimate grievance? If a legitimate grievance is a practical problem looking for a practical solution, where does the problem come from? Class resentment might be expected to come from a real class struggle in a society in which, oh, I don’t know, 10% of the people own 50% of the wealth. Is that a practical problem for Partridge? No, for him it’s a delusion because he was able to show that income inequality has ticked down ever so slightly in the last 10 years. For Partridge, Treaty politics are too identity-based and regressive. He would rather us just all focus on our shared vision for the future.

Partridge yearns for a return to the days of evidence-based solutions, shared facts, and a pragmatic approach. Those who have seen their material conditions steadily eroded over the last 50 years might wonder when in fact, politics have ever been typified by these conditions. It seems that Partridge is really asking for a return to a golden age when those who were hurt by the social and economic systems that privilege the wealthy few were unable to voice their opposition quite so stringently. It is ironic that much of the grievance he so decries is the direct result of a culture war waged as a cover for the foundational class war to keep the working class busy while the wealthy hoover as much wealth as they can from the public. The coalition Government’s entire policy agenda is class war writ large, with cuts and gutting of protections for workers, beneficiaries, disabled individuals and families, tenants, school kids, to name a few, while the rich get tax cuts and fast-tracked opportunities for more property, wealth, and investment. It’s staggeringly tone deaf how Partridge dismisses this as some type of petulant class resentment.

It is true that things have become more polarized. But it’s a symptom of the capitalist rot at the center of the system, rather than some fanciful revolutionary fantasy nurtured by radical leftists. By failing to correctly identify the material origins of the grievance he identifies, Partridge slips right into a more familiar form of grievance voiced throughout the ages by the ruling class against those unruly, uncouth, and uneducated working masses that keep complaining and agitating rather than quietly accepting their lot in life.

This is all to say nothing of the rather arbitrary starting point of 2007. Income inequality as measured by the Gini index increased roughly 10 points from 1984 to 1994 following the implementation of neoliberal reforms. It has leveled out since then, but only started decreasing in recent years. It has still come nowhere close to the lower level of income inequality seen prior to 1984.

I tried to write a letter to The Press / Post in response Hartwich's op-ed's bemoaning the end of the Liberal world order and how sad / frustrated he was. But I don't think the editor like my use of the word 'gaslighting'.

For those not 'Rich so I'm sorted' its bleeding obvious why we don't trust the rich, big business and government run by neolberals! They are untrustworthy, greedy, self-centered, cruel, cynical people! Big business operates for rich executives and even richer trust fund holders, asset management companies and global operators. What they do not do is operate for employees, the general public and in other words, the likes of you and me who are not 'Rich and sorted!'