Rosa Luxemburg was right

The revolutionary Marxist argued that capitalism's fundamental logic makes its replacement by social-democratic reform impossible. Her ideas are more relevant and urgent than ever.

As country after country lurches politically to the right and many are flirting with, if not outright embracing fascism, many are struggling to make sense of this shift in political climate. Liberal media outlets are bemoaning the death of democracy and the rise of authoritarianism and some are even claiming that this is the end of the old world order and that we are in the throes of a new world order being chaotically and violently birthed. The language of crisis and catastrophe is everywhere.

While the signs of what’s going on have been clear to those who are looking, the recent re-election of Donald Trump and his abrupt about-face from a faux populist to a nakedly corporate agenda has (hopefully) thrown back the curtain on whatever pretense was left to reveal that this is a good old-fashioned class war.

While many of his executive orders and policy proposals are driven by his own personal grievance, typical right-wing ideological positions, misogyny, and racism, underneath it all sits a foundational class war in which Trump and his corporate donors and handlers seek to funnel as much wealth from the American public into billionaire hands as possible.

This story isn’t new, even though its face changes with each generation. It’s as old as capitalism itself. What is important to understand is that the class war is not something that the working class thought up because one day they bought into the Marxist propaganda that they were oppressed, as so many right-wing pundits would have us believe. The class war, or class struggle, is an inextricable feature of capitalism itself. So long as capitalism exists, so will the class war. This is because capitalism rests on a fundamental antagonism between workers and capitalists. To understand, we need to examine the basic logic of capitalism.

How capitalism pits workers against capitalists

Marx defined capitalism as a “mode of production” which is just another way of saying it is a system by which people produce the material things (food, shelter, clothing) they need to survive. Because this is never (or very rarely) done in isolation, there is a social, or communal aspect to production. Marx refers to this process as social production. But it should be clear that the social aspects of production depend on and change with what Marx called the “material forces of production.” This is just another way of saying that the ways in which a society produces things—whether by hand, in homes, small workplaces, or large industrial factories—will necessarily change the social relations in that society. Marx put it like this

Social relations are closely bound up with productive forces. In acquiring new productive forces, men change their mode of production; and in changing their mode of production, in changing the way of earning their living, they change all their social relations. The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill, society with the industrial capitalist.1

Capitalism is a mode of production which is characterized by private ownership of the means of production. This is just another way of saying that under capitalism, the methods and resources necessary for people to sustain their lives are privately owned. Because of this, the majority of people in capitalist society are required to sell their labor in order to earn money to buy the things they need to sustain themselves. In other words, people work for wages. Capitalism is also characterized by a market economy which involves competition. The final ingredient is the profit motive. Capitalists are motivated to produce goods in order to generate a profit.

It is the three-way interaction between competition, wages, and profit that produces the fundamental and inescapable tension between workers and capitalists. Competition forces capitalists to reduce prices, and invest in technological innovation and increasing efficiency, which eats into their profits. Capitalists, in turn, in an effort to recoup the profits, decrease wages. Competition between workers for jobs also allows capitalists to decrease wages. Furthermore, since all profit is the result of capitalists paying workers less in wages than the value of their labor, capitalism rests on a fundamental exploitation of workers by capitalists. Or as Marx put it "The surplus-labour of the working class is the source of all wealth, of all capital, of all profit."2

Thus, workers and capitalists are forever locked into battle over wages and profits. This tension is the basis of class struggle and the reason socialists have advocated and worked towards the replacement of capitalism with a system that is not built on exploitation of workers by capitalists.

Socialism by another way

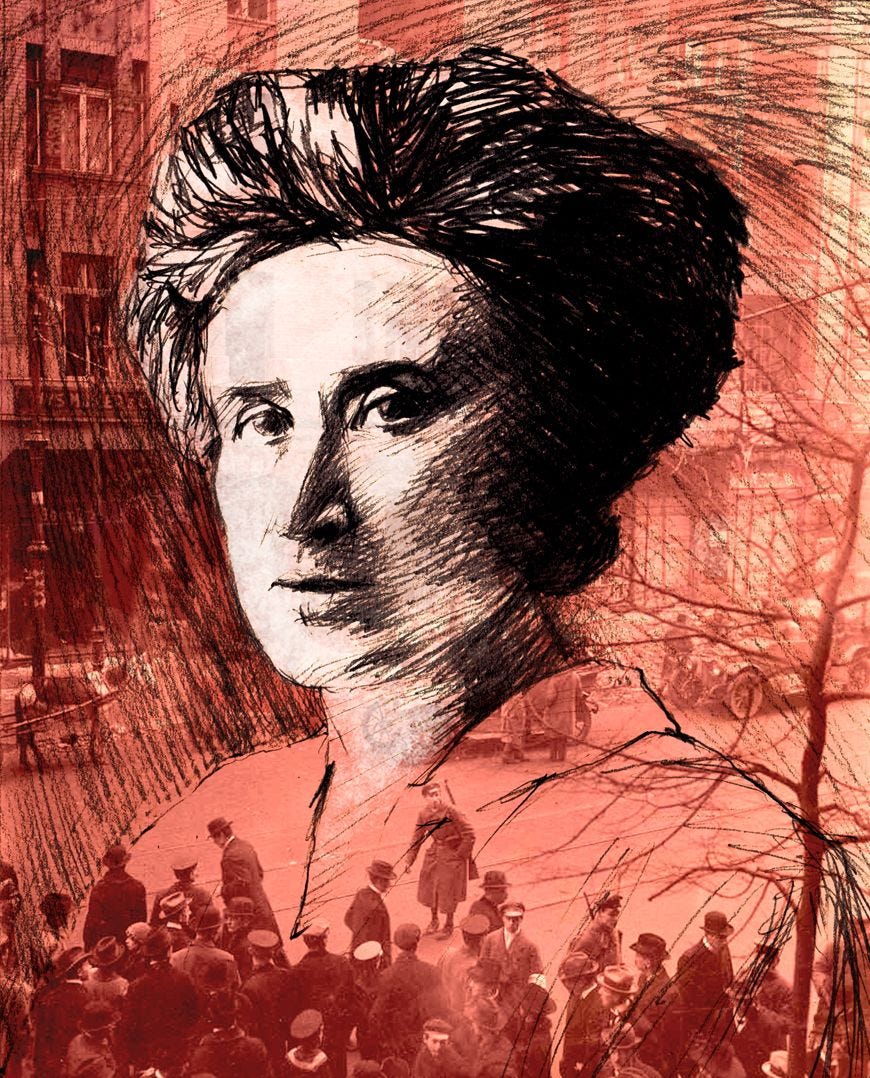

Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919) was a revolutionary Marxist theorist, organizer, and activist who participated in socialist movements in Poland and Germany in the early 1900s. A member of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), she was a critic of reform movements that claimed that socialism could be brought about by social democratic means, instead advocating strongly for a revolutionary socialist movement by which workers would take power. She argued that capitalism could not be reformed, but had to be overthrown and replaced with a system not based on exploitation. She believed this revolution would be the natural outcome of workers understanding the nature of the capitalist system and banding together against the capitalists.

Other members of the SPD, predominantly Eduard Bernstein, argued for a reformist socialist agenda. Bernstein was a Marxist and friend of Friedrich Engels who hoped to revitalize Marxism and free it from what he viewed as its problematic dogmas. The inevitability of capitalist collapse and replacement via revolutionary socialist activity was one of these dogmas.

For Bernstein, rather than being the result of revolutionary upheaval, socialism would be a natural result of a social-democratic process, in which capitalism would gradually evolve into socialism by normal social and political means. This could be brought about by legislative action on workers’ rights, progressive taxation, welfare programs, and other strategies that would blunt capitalism’s exploitative nature and the resulting inequality. Bernstein and other reformists emphasized the importance of working incrementally by normal democratic means towards an eventual socialism rather than upending the existing social and political order via revolution.

Luxemburg wrote a withering critique of reformism in her book Reform or Revolution, published when she was just 28 years old. The book takes aim at Bernstein specifically and attempts to disprove any evidence or arguments he presents in support of a reformist approach in favor of what she terms “scientific socialism.” For Luxemburg (and Marx) socialism was not just a utopian ideal that was strived for on the basis of some moral imperative, it was a natural outcome of the evolution in the means of production and capitalism’s own internal contradictions. For Marx, capitalism had evolved from feudalism, and socialism would evolve from capitalism as a matter of historical fact. Luxemburg argued that reformist approaches denied the fundamental historical materialism inherent in Marxism and viewed socialism not as a historical fact waiting to happen, but as a utopian ideal based on moral grounds

The fundamental idea consists of the affirmation that capitalism, as a result of its own inner contradictions, moves toward a point when it will be unbalanced, when it will simply become impossible… We have here, in brief, the explanation of the socialist programme by means of “pure reason.” We have here, to use simpler language, an idealist explanation of socialism. The objective necessity of socialism, the explanation of socialism as the result of the material development of society, falls to the ground.

Because of his discarding of historical materialism, Luxemburg questions Bernstein’s credentials as a Marxist, claiming that his theory is “in direct contradiction” to Marx’s fundamentals

Today he who wants to pass as a socialist, and at the same time declare war on Marxian doctrine, the most stupendous product of the human mind in the century, must begin with involuntary esteem for Marx. He must begin by acknowledging himself to be his disciple, by seeking in Marx’s own teachings the points of support for an attack on the latter, while he represents this attack as a further development of Marxian doctrine. On this account, we must, unconcerned by its outer forms, pick out the sheathed kernel of Bernstein’s theory.

Capitalist crisis and the state

One of Bernstein’s main critiques of Marx’s theory was the position that due to its internal contradictions and instability, capitalism would undergo more and more severe crises and would eventually collapse. He argued instead that capitalism had demonstrated its ability to adapt to such a degree that collapse was no longer inevitable, citing the development of credit and employers organizations.

Luxemburg argues that credit, far from being an adaptation that increases the stability of the capitalist system, actually makes it even more unstable. This is because capitalists use credit to increase production, but in the absence of a sure market, this leads to overproduction, which can lead to economic contraction. She also argued that because credit is not tied to anything in the material world, it encourages speculation on the part of capitalists, leading to unstable financial markets, speculative bubbles, and economic collapse. Employers organizations, or cartels, while they may stabilize some aspects of the domestic market, create and exacerbate competition in the global market, in addition to heightening the antagonism between workers and capitalists. Thus, Luxemburg argues that far from being means of adaptation which stabilize capitalism, these adaptations only increase the “anarchy of capitalism”, and make crises more likely.

The crux of the reformist position is that socialism can be realized through democratic means. Luxemburg quotes Konrad Schmidt’s vision for such reform

According to him [Schmidt], “the trade union struggle for hours and wages and the political struggle for reforms will lead to a progressively more extensive control over the conditions of production,” and “as the rights of the capitalist proprietor will be diminished through legislation, he will be reduced in time to the role of a simple administrator.” “The capitalist will see his property lose more and more value to himself” till finally “the direction and administration of exploitation will be taken from him entirely”...

Essentially, continual democratic reforms will remove the despotism of unregulated capitalism until the workers have all of the rights and protections they need and capitalists will lose their ability to exploit. But as Luxemburg notes, any reformist agenda which works to improve the lot of the working class will still be lobbying for improvements within the confines of the capitalist system, which is a fundamentally exploitative system. As Luxemburg notes, “Trade unions cannot suppress the law of wages.”

Schmidt and Bernstein’s reformism envisions the gradual transformation of the state into a representative of the working class that will “dictate to the capitalists the only conditions under which they will be able to employ labour power.” But Luxemburg questions such “mystification”

We know that the present State is not “society” representing the “rising working class.” It is itself the representative of capitalist society. It is a class state. Therefore its reform measures are not an application of “social control,” that is, the control of society working freely in its own labour process. They are forms of control applied by the class organisation of Capital to the production of Capital. The so-called social reforms are enacted in the interests of Capital.

In other words, the state is set up, according to Luxemburg, in the interests of capitalists. To assume that the state will allow itself to be transformed legislatively into a representative, advocate, or protector of the working class is folly of the highest order. The capitalist class may offer some concessions, but it is simply unrealistic to assume that they will participate in their own dissolution.

Thus, Luxemburg argues that all democratic and parliamentary processes actually postpone inevitably the arrival of socialism and the end of exploitation because the continued refinement and extension of capitalist society cements the power and influence of the ruling class at the expense of the working class. She is worth quoting at length here

The theory of the gradual introduction of socialism proposes progressive reform of capitalist property and the capitalist State in the direction of socialism. But in consequence of the objective laws of existing society, one and the other develop in a precisely opposite direction. The process of production is increasingly socialised, and State intervention, the control of the State over the process of production, is extended. But at the same time, private property becomes more and more the form of open capitalist exploitation of the labour of others, and State control is penetrated with the exclusive interests of the ruling class. The State, that is to say the political organisation of capitalism, and the property relations, that is to say the juridical organisation of capitalism, become more capitalist and not more socialist, opposing to the theory of the progressive introduction of socialism two insurmountable difficulties… The production relations of capitalist society approach more and more the production relations of socialist society. But on the other hand, its political and juridical relations established between capitalist society and socialist society a steadily rising wall. This wall is not overthrown, but is on the contrary strengthened and consolidated by the development of social reforms and the course of democracy. Only the hammer blow of revolution, that is to day, the conquest of political power by the proletariat [working class] can break down this wall.

Practical reforms vs revolutionary transformation

Luxemburg then turns to a discussion of the practical implications of different views of how to establish socialism. She criticizes Bernstein’s reformism as lacking a definitive goal (the establishment of socialism) and being instead concerned with only individual successive reforms, pointing to his famous quote “the movement is everything, the final goal is nothing” as evidence that he has lost the end goal of socialism in favor of incremental reforms. She stresses that it is of the utmost importance to always have the end goal of taking political power in mind, rather than be content with practical outcomes.

As soon as “immediate results” become the principal aim of our activity, the clear-cut, irreconcilable point of view, which has meaning only in so far as it proposes to win power, will be found more and more inconvenient. The direct consequence of this will be the adoption by the party of a “policy of compensation,” a policy of political trading, and an attitude of diffident, diplomatic conciliation. But this attitude cannot be continued for a long time. Since the social reforms can only offer an empty promise, the logical consequence of such a program must necessarily be disillusionment.

Once disillusionment sets in, the realization of a transformation of society will be lost and the capitalist order will be reified and reinforced. Transformation, not singular political victories, must be the continual goal. Luxemburg argues that Bernstein’s reformist views are only possible because he has engaged in historical revisionism as to the real character of the capitalist system. He has contented himself with believing that capitalism’s adaptability has rendered it immune to crisis, therefore the only way to improve the lot of workers is by working for reform within the capitalist system. After all, if the system’s contradictions will not lead to an inevitable crisis, the opportunity for a revolutionary political transformation will not present itself either.

Luxemburg excoriates such revisionism, claiming that Bernstein is a capitalist apologist and his reformist revisionism essentially renders the labor movement null and void with regard to any real change for the working class.

It is not true that socialism will arise automatically from the daily struggle of the working class. Socialism will be the consequence of (1), the growing contradictions of capitalist economy and (2), of the comprehension by the working class of the unavoidability of the suppression of these contradictions through a social transformation. When, in the manner of revisionism, the first condition is denied and the second rejected, the labour movement finds itself reduced to a simple co-operative and reformist movement. We move here in a straight line toward the total abandonment of the class viewpoint.

Luxemburg concludes with a discussion of the absolute necessity for a revolution in which the working class takes power and transforms society. But she also clarifies that revolution and reform are partners in this process.

Every legal constitution is the product of a revolution. In the history of classes, revolution is the act of political creation, while legislation is the political expression of the life of a society that has already come into being. Work for reform does not contain its own force independent from revolution.

She further argues that reform will not accomplish the necessary changes to society because the exploitation inherent in capitalism is not codified legally. There is no law codifying “wage slavery” or the requirement for people to work for wages. Luxemburg argues that the fundamental difference between capitalist society and all other historical forms of society is that the

class domination does not rest on “acquired rights” but on real economic relations – the fact that wage labour is not a juridical relation, but purely an economic relation. In our juridical system there is not a single legal formula for the class domination of today… No law obliges the proletariat to submit itself to the yoke of capitalism. Poverty, the lack of means of production, obliges the proletariat to submit itself to the yoke of capitalism. And no law in the world can give to the proletariat the means of production while it remains in the framework of bourgeois [capitalist class] society, for not laws but economic development have torn the means of production from the producers’ possession.

How can legislative and legal reforms change a system in which the fundamental aspects of exploitation are not legally codified, but rather exist as an intrinsic aspect of the economic and social relations of that system? Simply put, they can’t. The exploitation of capitalist society is beyond the reach of reform because it results from the fundamental elements of capitalism. This is Luxemburg’s most forceful point against the effectiveness of a reformist strategy. Thus, while reforms can change society progressively towards the form envisioned by socialists, these reforms will always butt up against the reality of the capitalist social and economic system that they are attempting to change.

Because reforms are always constrained by the existing social systems in which they are being pursued, Luxemburg argues that the reformist strategy cannot lead to socialism, it can only lead to different forms of capitalism. Revolution is the only way to transform the system. In fact, Luxemburg argues that Bernstein and other reformists have wholly abandoned any aspirations towards socialism with their revisionism and rejection of Marxism and its principles and analyses and are simply defenders of capitalism and capitalist apologists.

Why Rosa was right

The questions that Luxemburg addresses in Reform or Revolution seem particularly relevant today. For one, the idea that capitalism has adapted itself to the point where it will not face periodic crises has been definitively disproven. The Great Depression and the Global Financial Crisis have proven that capitalism is an inherently unstable system. In both cases, the state intervened to stop the capitalist system from wholesale collapse. The collapse of global supply chains during the COVID pandemic is further evidence of the fragility of the global capitalist system.

The failure of legislative reform to effect lasting change has also been clearly demonstrated. In the wake of the Great Depression, FDR’s New Deal set up a welfare state that led to an era of prosperity, but this was not a repudiation of the capitalist system. It was rather a legislative gambit to save the capitalist system from itself. The decades since have seen the capitalist class claw back most of the gains made by workers via judicial activism and political and legislative victories. The last 50 years of neoliberal capitalism has seen the gutting of workers’ protections and organized labor, privatization of the public sector, tax cuts for the wealthy, and an upwards transfer of wealth and explosion of inequality not seen for 100 years. These political victories by the capitalist class represent the culmination of a class war that was intensified with the New Deal.

Such is the nature of a reformist approach. Reforms can go both ways, and as history and the current political turmoil have revealed, when the capitalist class feels threatened by too many working class reform successes, they hit back. Hard. The result is a gutting of the labor movement, authoritarianism, and fascism. The nominally left Democratic party has been wholly captured by capitalist interests and has been complicit in the destruction of the labor movement and stripping back the welfare state. As evidenced by their complete and total capitulation to the new Trump administration while offering a long stream of platitudes and excuses, their loyalties lie completely with the capitalist system. The judicial system has also been captured by capitalist interests and has legally enshrined a bulwark against working class interests, together with an international web of legal tribunals and organizations that serve to insulate capitalism from any democratic threat. The facade of democracy can only be pushed so far before the true nature of the state as capitalist caretaker and guardian is revealed.

Here in Aotearoa, a newly-emboldened right wing is moving at lightning speed to dismantle democratic protections for workers and to funnel public wealth into private hands. The cautious incremental reforms under Ardern’s supermajority were embarrassingly inadequate and have been rapidly rolled back. The capitalist class, on the other hand, is never shy or timid in implementing its agenda, regardless of public and popular opinion or wishes. Capital issues its voracious mandate in perpetuity.

This is why reform is not enough. Revolution is the only way.

Luxemburg remained a revolutionary for the rest of her life, which was cut short after the failed Spartacist Uprising by rightwing paramilitary troops. She lived and died working towards the hope that the working class would realize their power. She believed that the contradictions and crises of capitalism would provide a historical opening for workers to seize political power and transform the system for the benefit of all. She saw, more clearly than most, that maintaining that revolutionary goal in mind provided the power and imagination to keep going in the face of myriad setbacks and losses. Her searing and incisive work and her unbreakable revolutionary spirit is needed today more than ever.

Read Reform or Revolution today. Form a Marxist book club. Reading guide and questions here.

Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy.

Marx, Value, Price, and Profit.

Great article. I’m particularly interested in why we don’t take the opportunities that crisis allows? Why people don’t seee the contradictions? And why the left has lost all energy & ideas.

Thank you for making me think

This is good and timely for me as I was just thinking about creating a post about how all of this clusterfuck chaos really boils down to two words: late capitalism. The American system, being premised on LC, has spawned the white collar criminal politician and technology has given it the ultimate weapons of social control colluding with the already feudal class comfort zone mind control of the religious masses.

However, before we start shouting "Viva la revolution!" consider the impact of emergent AI on "labor" for a minute. First, let me clarify that I am aware that most of what we hear about it is pure hype and there are some great books and podcasts by programmers and tech writers explaining the reality of it versus the hype that the general public gets. I myself have done presentations on this topic discussing the human drives and analyzing the 80 years of the attempt (aka digging the hole that you can't stop digging) to create AGI from a humanities perspective.

But, now I have realized a motivation that I had not thought of even though it is right in front of me: replacing the workers so they can't revolt in a way that serves their survival.