No, capitalism has not lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty

The common narrative of progress relies on an economic sleight of statistical hand and a selective historical analysis that sanitizes capitalism's brutal human toll

Update - 2/21/2025

Since making this original post (by far the most popular on my new little Substack) there have been many comments, some in good faith, and some not so much. These comments and discussions have made me realize that I have not been as clear on a few things as I had hoped. Because this topic is very emotionally-resonant and has been politicized to such an extent, my last wish is to add more confusion or to spread an argument that is not empirically-based or simply dogmatic. After thinking about it the last 10 days, I want to clarify my position on a few things.

First, I had no idea Hickel was such a lightning rod. I used his work because I know he is probably the most popularly-known and accessible scholar doing this type of work. I note that many of the criticisms that he has made about calculation of poverty lines have been made by others as well, and I’ve cited them throughout the essay. But after doing some more digging, it seems that for a variety of reasons, Hickel’s work and engagement in this area are controversial. I want to acknowledge that up front.

Second, while I stand behind what I’ve written, I do not want to give the impression that poverty has not been reduced since the 1820s. While the specifics differ across different geographical regions and social and political arrangements, the general trend is that poverty has indeed decreased. The question for me is whether the measures used to index the decrease reliably capture the material conditions of those indexed, and whether other measures show the same decrease in poverty. This is clearly not a settled matter.

The point of the post was to show that the familiar narrative of capitalism decreasing poverty is overstated and much more nuanced. On the other hand, to say that free-market economies (not the same thing as capitalism) have not contributed to economic growth and poverty reduction is simply burying our heads in the sand. Our legitimate criticisms of capitalism will not be taken seriously if we can’t even admit to this fact.

My point in this foreword is to make it clear that many measures of poverty have shown decreases since 1820. That is a fact. Globalization and market economies have played a role, as has increased state expenditure on poverty reduction and progressive policies and movements that have mitigated the most damaging impacts of unregulated capitalism. Much more work needs to be done to tease apart the specific nature of the reductions, and whether they are sustainable given the push toward unregulated capitalism.

Given my personal opinion on capitalism, which will be obvious to anyone who reads my stuff, I may have come across to some readers as more polemical than I intended. I think there are enough data showing the harms that capitalism has caused without resorting to exaggeration or selective historical analysis. I hope this post moves the conversation forward in a productive way. It will not do any good for us to simply retreat to our ideological corners.

Anyone who criticizes capitalism can be assured that they will be hit with this little rhetorical gem, repeated without scrutiny or due diligence by Western governments, media, philanthropists, journalists and authors, right-wing think tanks, and your average conservative voter alike:

“If capitalism is so bad, why has it lifted hundreds of millions (billions, depending on who you talk to) out of poverty?”

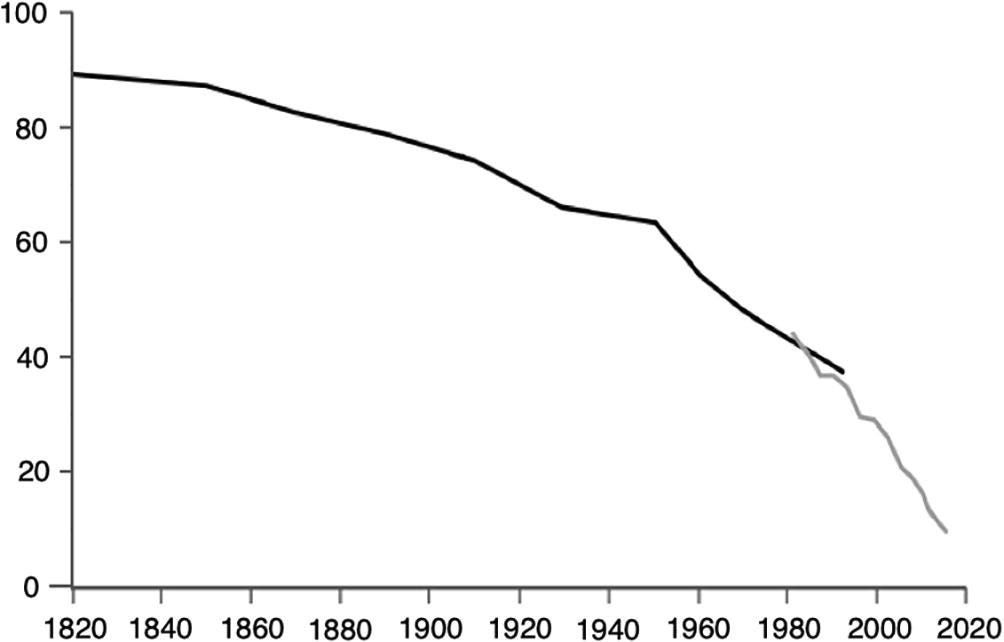

Those of us who have been hit with this one over and over (and it is the go-to for capitalist apologists) can sometimes feel a bit like a deer in the headlights. Something about it doesn’t quite feel right. After all, there are reams of data suggesting that many facets of human existence, wealth inequality for starters, have gotten much worse under capitalism. So something about this claim feels wrong, but there also appear to be reams of data from the World Bank and others indicating that poverty has indeed gone down since capitalism and free markets were introduced to the world (see figure above).

If we are to make a serious case for the incompatibility of capitalism with human flourishing, we need to understand and be able to discuss this most pervasive of capitalist myths.

So let’s get started.1

Moving the goalposts

The story starts in 1996, when the world’s governments got together in Rome for the World Food Summit. In this meeting, they pledged to end extreme poverty. Specifically, they pledged to cut the number of undernourished people by half by the year 2015 (cutting the number by 836 million people).

The next time any real fanfare was made of this goal was at the United Nation’s Millennium Declaration in 2000. In this declaration, the UN pledged

To halve, by the year 2015, the proportion of the world's people whose income is less than one dollar a day and the proportion of people who suffer from hunger

Already we can see a subtle shifting of the goalposts here. The Rome summit of 1996 pledged to halve the number of undernourished people in the world. The UN’s goals pledged to halve the proportion of the world’s people who have an income of less than one dollar per day and the proportion of people who suffer from hunger, starting at the baseline year of 2000. As explained by Jason Hickel

By switching from absolute numbers to proportions, the target became easier to achieve, simply because it could take advantage of population growth. As long as poverty was not getting much worse in absolute terms, it would automatically appear to be getting better in proportional terms.

This subtle shift therefore meant that rather than having to cut the number of those in poverty by 836 million, the new goal meant having to cut it by only 669 million people, something that was much more manageable.

When the goals were formalized as the Millennium Development Goals by the UN shortly after the Millennium Declaration, there was another subtle shifting of the goalposts. First, the poverty goal was now to halve the proportion of those in poverty in developing countries only. Because the population in developing countries grows at a faster rate than the world as a whole, this allowed poverty calculations to take advantage of the rapid population growth to inflate their poverty reduction stats. Second, rather than have a benchmark year of 2000 (when the Millennium Development Goals were formulated) the analysis would now take place beginning in 1990, a full ten years earlier.

Together these two changes allowed the UN to both dilute their original goal (from cutting the number of people in poverty from 836 to 669 to finally 490 million) and portray their progress on the poverty goal as much more robust than it actually was, taking into account any reductions in the decade from 1990 to 2000.

The shifting international poverty line

How do you tell if someone is living in poverty? Historically, separate nations have calculated their own “poverty line” or the average cost of all essential resources for subsistence of an adult. Given the wide variation in many factors across social, cultural, and economic contexts, for many years it was assumed that there was no real way to compare this metric across different countries. Nevertheless, the World Bank really wanted to find a common metric by which to measure poverty across the world. An economist named Martin Ravallion noticed that the poverty lines of some of the world’s poorest countries were all pretty close to $1.02 per day. He, and the World Bank, thought this was reason enough to set an international poverty line (IPL) at $1 per day, and they adopted this as their first IPL.

There was only one problem, and that was that when the data were in at the end of 2000, using an IPL of 1$ per day showed that the absolute number of people living under less that $1 per day was rising. It had increased from 1.2 billion in 1987 to 1.5 billion in 2000, and was projected to increase to 1.9 billion by 2015.

This news was a big problem for the World Bank, the UN, and all of the free market advocates who had claimed that capitalism, and particularly the neoliberal policies of the 80s and 90s that had been forced on the Global South by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, had ushered in an era of unheard-of prosperity.

But soon after the annual report declaring that poverty had increased, the president of the World Bank made a speech declaring just the opposite. In fact, he said, poverty in developing countries had actually decreased during that same period. Three years later, the World Bank published its new figures. Astonishingly, 400 million people had been lifted out of extreme poverty in the period from 1981 to 2001.

What is going on here? How can the same organization, using the same data, go from bemoaning the increase in poverty to hailing its decrease, even surprising itself by how big the decrease was?

It’s easy. All you have to do is change the poverty line.

In 2000 the World Bank increased its poverty line from $1.02 per day to $1.08 per day. While this small change may seem insignificant, based on the way that the calculation of the IPL works, with changes meant to account for things like inflation and decreasing purchasing power, it actually was lower in real terms

If the purchasing power of the dollar goes down, people need more dollars to buy the same stuff as before. So the poverty line needs to be periodically “raised” to account for this. But in this case they didn’t raise it quite enough to account for purchasing power depreciation. So the new $1.08 poverty line was actually lower in real terms than the old $1.02 line. And lowering the poverty line made it appear as though fewer people were poor than before. When the new line was introduced, the poverty headcount fell literally overnight, even though nothing had actually changed in the real world.

The World Bank changed its poverty line once again to $1.25 per day in 2008. While this increased the absolute numbers in poverty by 430 million in 2008, when applied to the entire dataset from 1990 onwards, it actually increased the number of people lifted out of poverty by 121 million, from 316 million to 437 million. It made the overall trend look better. So the World Bank went with the new IPL.

It should be clear that on the face of it, this statistical jiggery pokery is deeply disingenuous and amoral if not immoral. It is completely removed from any real outcomes in the lives of real people. If the click of a button can change the statistical estimate of poverty by 430 million people without any regard for whether the material circumstances of these people have actually changed, this definition of poverty is fundamentally flawed.

Is survival enough?

Aside from the shady history of adopting changing IPLs when they just so happen to make the narrative of capitalist progress and poverty reduction look better, the IPL has come under fire for other reasons.

The most important is that it severely underestimates poverty and associated deprivation. Putting aside whether national poverty estimates are reliable (due to lack of data, political engineering, etc…) a comparison of even just a few examples shows that the World Bank’s IPL very often underestimates poverty.2

In 1990, the Sri Lankan government reported 40% poverty; the World Bank reported 4%

In 2010 the Mexican government reported 46% poverty; the World Bank reported 5%

In 2011 researchers in India reported that 680 million people lived in poverty; the World Bank estimated 300 million

In India a child living just above the IPL has a 60% chance of being underweight

In Niger children born to families just above the IPL have a mortality risk of 160/1000; more than three times the world average

There are many more data like these. They show the utter unseriousness of the World Bank’s IPL as a practical measure of poverty. If those who live just underneath or above the IPL do not have a realistic chance of having a normal human life, what good does lifting anyone above this line do in real terms? If people living above the IPL count as “hungry” by the UN’s own standards because they are not able to get the essential nutrients they need, can they really still fit any realistic criteria for not being in poverty?

These data call into question the entire premise on which claims of global poverty reduction are made. Indeed, when other poverty metrics are used, the data show that poverty and deprivation have increased, rather than decreased, since the 1990s. In 2015, according to one estimate, over 60% of the world’s population lived under the ethical poverty line.

What about China?

One of the reasons the UN shifted its starting year for the Millennium Development Goals from 2000 to 1990 was so it could take advantage of the purported massive reductions in poverty in China since their implementation of capitalist reforms. Indeed, China is held up by many right-wingers as hard evidence of capitalist success (even though they tend to hate China also for this reason due to its superior competitive edge in the world market). You can see why the World Bank wanted to include China in its calculations from this figure

This would seem to validate the claims of the free-marketers. Once China liberalized its economy and adopted free-market reforms, including privatization of public services, the percentage of the population living in poverty plummeted. Another victory for the free market.

But the actual details of China’s economic and poverty miracle are much less appealing to capitalist apologists.

First, China adopted free market reforms slowly, on its own terms, as suited the economy and social and political practicalities. This was a far cry from the neoliberal reforms that were forced onto much of the Global South by the World Bank and IMF in the 80s and 90s under the innocuous branding of “structural adjustment”, a recipe which required privatization, austerity, and deregulation. Indeed the success of China’s reforms can be attributed to its ability to implement market reforms, state ownership, investment, and protectionist policies according to their own political and economic needs.3 According to economic historian Quinn Slobodian

In contrast to the shock treatment meted out by Augusto Pinochet to Chile after his 1973 coup, or the Big Bang overnight price reforms carried out in postcommunist Russian and Eastern Europe, China used a model of “experimental gradualism,” opening up sluices and locks to foreign investors and market-determined prices rather than dynamiting the levee and letting it all flood in.4

So that’s strike one for the free marketers. China’s capitalist rise involved a much higher degree of protectionism and state planning than your typical libertarian would like to admit.

However, a recent study questions not just the mechanism of China’s poverty reduction, but the reduction itself. To date, all of the claims of China’s reduction of poverty under capitalist reforms have been based on the World Bank’s IPL. Given the problems with the IPL in accounting for actual standards of living, poverty, and deprivation, a group of researchers calculated poverty another way, according to the “basic needs poverty line.”5 The BNPL is useful because it compares income against the cost of basic needs. This comparison can vary from context to context. Thus, the BNPL provides a more accurate assessment of poverty than the IPL.

When the researchers used this metric to estimate poverty in China, their results were surprising. They found that in the years before the free-market reforms (1981-1990) the percentage of people in extreme poverty was only 5.6%. During the neoliberal reforms (gradual as they were) of the 90s, poverty rose sharply to a maximum of 68%, and this corresponded with a large increase in the price of commodities with privatization. Altogether the researchers concluded that

These results indicate that socialist provisioning policies can be effective at preventing extreme poverty, while market reforms may threaten people's ability to meet basic needs.

Capitalism, resistance, and poverty

The common narrative supported by capitalist apologists is that, prior to the rise of capitalism, the vast majority of the world lived in a state of poverty. With the rise of capitalism, wealth increased and so did standards of living for everyone. We basically went from 90% poverty to 10% in 200 years. It’s the whole rising tide lifts all boats thing. This story seems to be supported by popular graphs like the one found at the top of this post and in Stephen Pinker’s book Enlightenment Now.

Aside from the problems noted above with the use of the World Bank’s IPL to calculate poverty, another issue is that the figure begins in 1820, which is the height of the Industrial Revolution. But many historians and scholars point to the 15th and 16th centuries as the time when capitalism really began. The three centuries before 1820 was a time of massive colonialism, expropriation, dislocation, enclosure, enslavement, and genocide of indigenous populations. These events and actions paved the way for the Industrial Revolution by, among other things, transferring a massive amount of wealth from the Global South to Europe. These facts and data are not included or accounted for in the above graph.

Getting accurate poverty data from so long ago is difficult, but researchers have been able to gather proxy data for poverty. Measures like real wages, human height, and mortality can give an approximation of living conditions even in the absence of explicit poverty data.

When researchers analyzed these metrics for countries in Europe, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and China, they found that rates of poverty (lack of access to basic needs for subsistence) sharply increased with the rise of global capitalism and colonialism. While the patterns varied qualitatively across regions, what is clear from the data is that the decrease in global poverty since the Industrial Revolution corresponds with the rise of organized labor movements and progressive and anti-colonial efforts against capitalism. They conclude

Contrary to claims about extreme poverty being a natural human condition, it is reasonable to assume that human communities are in fact innately capable of producing enough to meet their own basic needs (i.e., for food, clothing, and shelter), with their own labour and with the resources available to them in their environment or through exchange. Barring natural disasters, people will generally succeed in this objective. The main exception is under conditions where people are cut off from land and commons, or where their labour, resources and productive capacities are appropriated by a ruling class or an external imperial power. This explains the prevalence of extreme poverty under capitalism…

The evidence reviewed here suggests that, where poverty has declined, it was not capitalism but rather progressive social movements and public policies, arising in the mid-20th century, that freed people from deprivation.

Conclusion

Simply put, the narrative of capitalism as the driver of decreased global poverty does not stand up to historical fact or methodological scrutiny. Those perpetuating this narrative do so in an effort to justify an unjustifiable social and economic system that allows a minority of people to extract and hoard wealth from the majority.

Even if the World Bank’s flawed metrics were useable, what does it say about our society that in a day and age when global wealth is greater than $454 trillion, we still have over 700 million people living in poverty? What does it say about us as a society when the personal fortunes of the ten richest men in the world doubled during COVID, while the incomes of 99% of the rest of the world fell? What does it say about us when the first person is predicted to achieve trillionaire status in 2027 while roughly 27 million will die of hunger or hunger-related diseases from now until then?

Regardless of the metrics, we have failed. We will continue to fail until we realize and admit that a system that prioritizes wealth and profit cares nothing for poverty. The World Bank may manipulate poverty lines to hide the truth that its demands for free market structural adjustments have immiserated millions of people, but as inequality continues to grow, it’s getting harder and harder to hide the reality behind the economic and statistical sleights of hand. Despite much work by the World Bank’s economists and others, the fundamental flaws with the IPL remain a serious issue. Much more research needs to be conducted using more valid and humane metrics of poverty to understand the real relationship between adoption and implementation of free-market capitalist reforms, their interactions with different social and cultural milieu, and the impacts on poverty throughout history.

In terms of actually addressing poverty in the world today, it is clear that our current strategy is not working. Rather than focus on illusory measures of poverty or unrealistic economic growth scenarios which will lead to climate tipping points, we should focus all our efforts on reducing wealth inequality, as redistribution of wealth will do more to alleviate poverty sooner than simply waiting for the economic pie to grow large enough for all to be able to afford to eat.

This post is indebted to the work of Jason Hickel. While not without his detractors, I think anyone who is serious about understanding these arguments should read his book The Divide: A Brief Guide to Inequality and its Solutions.

These examples come from Hickel’s book, The Divide, published in 2017. Some of the stats reported may have changed in the time since then.

It should be noted that the US and British economies developed along these same lines. Free trade and protectionist policies went hand in hand and were utilized as necessary to guarantee a strong economy and development. This is something the West has explicitly denied to the Global South.

Slobodian, Crack-Up Capitalism, 28.

Allen, R.C., 2017. Absolute poverty: when necessity displaces desire. American economic review, 107 (12), 3690–3721; Allen, R.C., 2020. Poverty and the labor market: today and yesterday. Annual review of economics, 12, 107–134.

A few points:

1) There's no need to quibble about the poverty line, which is fundamentally arbitrary. The neolib “line go up, world get gooder” applies to tangibles, line literacy rates, child mortality, life expectancy, etc. The material condition of the human species has massively improved since the industrial revolution and it's borderline insane to deny this.

2) A relative decline in poverty, even if not absolute is still Very Good regardless of whether one is a total or average utilitarian and reflects well on the economic order under which it occurs.

3) Arguing about whether capitalism began with colonialism, the industrial revolution, or something in between seems like a word game. People aren't posting the line go up graphs and saying “See? This is why we should do the Scramble for Africa 2.0.” People are advocating for the market economy as it has existed ~since the end of WW2.

4) Comparing wealth inequality to pre-captialist eras is extremely fraught because making 1:1 comparisons of asset values potentially flattens a lot of historical economic and social distinctions.

5) Yes, China and other developing countries that succeeded had industrial policies, tariffs, etc. But (a) a Marxist would still call these systems “capitalist” and (b) that's not necessarily *why* they succeeded. In pairwise comparisons of like counties, the more laissez-faire ones generally do better (South vs North Korea, Botswana vs Zimbabwe, West vs East Germany, etc. You can accuse me of cherry-picking, but I honestly am not aware of any plausible pairwise comparison where the results are the opposite)

***

I say this as a liberal and a supporter of the market economy, but I'm not really trying to “dunk” on any socialist alternative. I think people who use “line go up” as a slam-dunk argument against any socialist alternative are being intellectually lazy. But it's annoying when socialists pretend, for ideological reasons, that the massive improvement in material conditions over the past century and a half has nothing to do with markets or just isn't real. There are plausible socialist alternatives to capitalism, and plausible arguments for their desirability, that aren't cancelled out by the above facts.

The author has clearly never been to China.

I would also point out that Capitalism has lifted hundreds of millions of Europeans (and people living in former European colonies) out of poverty. It did so for about 100 million Japanese people and about 50 million Koreans, too. How many hundreds of millions living outside of poverty in a global capitalist economy would you have to see before you believed the claim, “Capitalism has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty”?

This piece commands of its readers, “don’t believe your lying eyes.”