Why do we always learn the wrong political lessons?

Basic learning theory helps us understand why we are so susceptible to manipulation by political narratives and rhetoric

The rise of capitalism has almost wholly captured our moral frameworks and values in such a way that it moves unnoticed in almost all areas of our lives. The logic of capital has infused our political systems and language with meanings and definitions that serve to perpetuate policies and systems that are favorable to it. Furthermore, the language of traditional morals and values has been associated with capitalist values and market logic, particularly since the beginning of the neoliberal era, such that the use of this language evokes these capital-friendly definitions and associations without our even knowing it.

My argument is that these associations drive our almost automatic acceptance of policy and governance that is not in the best interest–in fact is grossly harmful–to the vast majority of us while it serves to benefit a handful of wealthy individuals and corporations. I’ve written about how this has been an explicit goal and program of these interests a lot. A lot of us have some kind of inkling that business and wealthy interests are really not in it for us, and we read news stories all of the time about how governments are corrupted by such interests. But many of us who are hurt by these political maneuverings still support politicians, parties, or policies that hurt us materially and socially. Why do we never seem to learn?

Defining learning

Taking a step back from the political arena, it may be helpful to examine the basic psychological processes by which we learn. This will then help us to connect the dots between ourselves as learners, politicians and special interests as manipulators of that learning process, and what we can do to become more accurate and responsible in our approach to our political learning.

Basic learning theory examines the evolutionary, biological, and contextual features of a given organism and situation that impact how it will learn and how do the consequences of our choices impact future behavior in similar or different situations? This is different from a focus on decision making. Decision making is predominantly the realm of cognitive psychology. It focuses on cognitive processes and mental states and their interactions in producing the decisions that people make in a given situation. Basic learning theory focuses much less on the specifics of the mental lives and activities of the learner and more on the environmental features and learning mechanisms that come to control behavior in a given situation, although the lines between cognitive psychology and basic learning theory are often blurry, particularly as both become more and more dominated by neuroscience.

Learning can be defined in a number of ways but for our purposes it will serve to begin with a very general definition. Learning is the process by which we try to determine the relationships between things in the real world. From an evolutionary perspective, an organism that fails to correctly learn such relationships will not live long enough to pass on its genes. There are a number of biological mechanisms and psychological processes by which we learn but I will focus on two: Bayesian updating and associative learning. Both of these theoretical approaches are attempts to explain how we come to understand the world. They are both very relevant to understanding why our political choices do not often accurately track political and material realities.

Bayesian updating

Learning involves changing our behavior or beliefs about something based on experience or new information. Bayesian updating (named for the mathematician who derived Bayes’ theorem) is a formal statistical method that specifies how newly-learned information is integrated with prior belief to update our understanding in a given situation. Mathematically it is based in probability theory but a conceptual understanding is sufficient for our purposes.

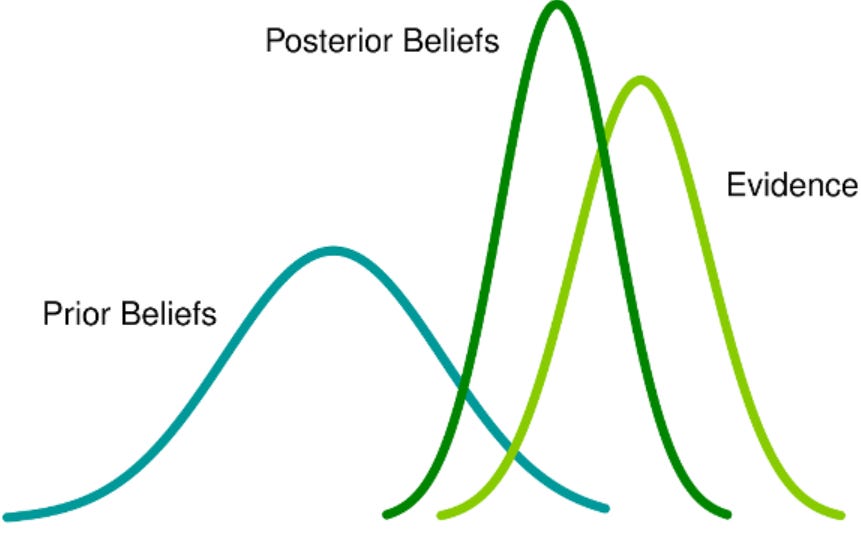

In any given learning situation there are three key aspects: 1) our prior expectations or beliefs about the state of reality, 2) the evidence we receive about the actual state of reality, and 3) our updated understanding and belief (posterior belief). Figure 1 shows the relationship between these elements of a learning experience. For example, consider an animal that lives by foraging. Having approached an area where it has found food multiple times in the past its prior expectation is that it will find food there. However, the patch has been depleted by other animals and so there is no food to be found. Based on this experience, the animal updates its belief about food being available in this location and will be less likely to forage there in the future. With successive experience and evidence, the belief more and more approximates the state of reality.

Although this is a fairly simple example, a large body of evidence indicates that learning can be described by this general process. The critical factors are the strength of our prior beliefs and the strength of the evidence we receive. If our prior beliefs are very strong or the evidence we receive is weak then our updated understanding will not reflect the state of reality. There is a lot of research being done on how the relevant prior expectations are formed and what impacts the strength of evidence in a given learning situation.

Associative learning

The foundation of associative learning is that things that occur together often have biological or evolutionary significance. Things that occur closely in time or in space are often related in such a way that paying attention to them is beneficial, often critical. For example, an animal that hears a rustling in the bushes before being attacked by a predator learns to heed the rustling bushes in the future. Because the attack came directly after the rustling, the rustling becomes predictive of the attack. Organisms have evolved to associate predictive events with their consequences.

Associative learning allows organisms to avoid aversive or dangerous consequences such as a predator attack. In our example, if the animal survives the attack it will be more attuned to the bushes in the future. It may avoid foraging or feeding near the bushes altogether.

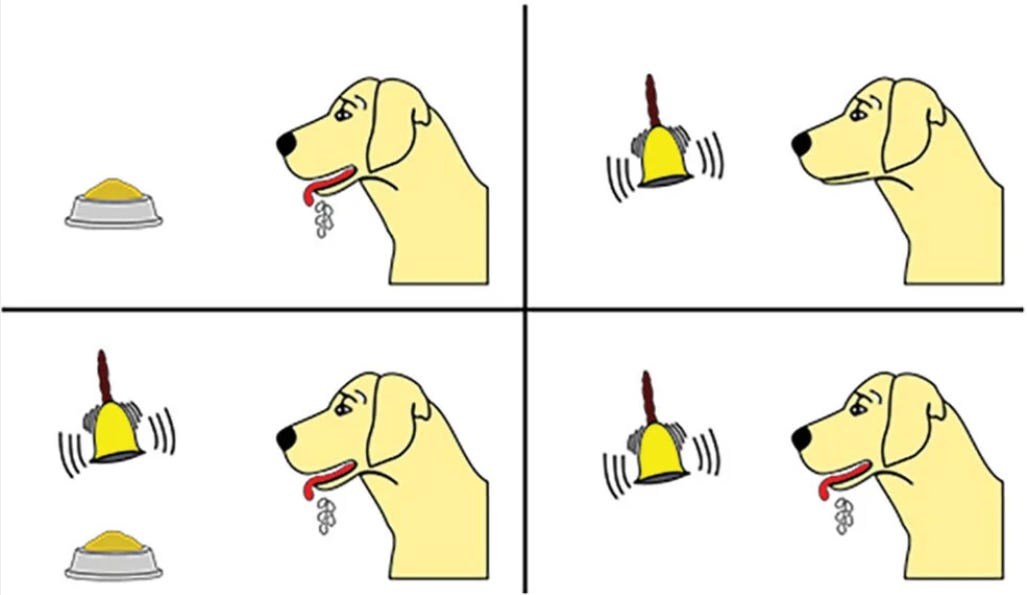

Associative learning also works with positive consequences. The most famous example is that of Pavlov’s dogs (Figure 2). This was a series of experiments where Pavlov found that if you pair the ringing of a bell with the delivery of food to a dog, the bell eventually comes to elicit the same response as the food (salivation). This even occurs in the absence of food. By being paired, or associated, with the food, the bell has come to take on some of its psychological properties.

Many other studies have shown that the probability of a behavior being performed in the future increases if it is followed by a reward. Likewise, the probability decreases if the behavior is followed by punishment. The effect is greater the closer together in time the behavior and consequence occurs and the easier it is to discern the contingency, or causal relationship, between events. Returning to the bush example, if the predator rustles the bushes and a bird squawks loudly and a thunderclap booms right before the attack, it will be more difficult to appreciate the rustling bushes as the important event.

These examples illustrate the crucial feature of associative learning: pairing. We are evolutionarily prepared to associate things that are paired together. Associative learning is ubiquitous in our lives and can produce long-lasting emotional or behavioral consequences and patterns. Take a minute to think about examples from your life. You may have locations, such as the beach, that you love to be at. These locations may evoke a happy, contented feeling that suddenly comes upon you when you smell something that reminds you of the beach. You may have eaten something that made you sick. Chances are you avoided that food afterwards. We may try to motivate our children to clean their room by offering an ice cream or movie. Someone who experienced a car crash may avoid driving by the location where it occurred. People who use drugs are more likely to overdose if they use in a different location than normal. Many of us, even as adults, revert back to old ways of acting or communicating when we return home to visit our parents. You may have negative feelings toward certain groups or individuals which are automatically evoked when they are mentioned.

You can see how associative learning plays a huge role in many aspects of our lives. The key thing to remember is that associative learning occurs whenever something is paired with something else. This is because such pairing has had predictive utility in our evolutionary past. Crucially for our present discussion, however, the associative pairing need not have evolutionary utility to be learned. Anything that is paired enough times, either actively or passively, has the potential to form an associative link. In addition, and of direct importance to our current discussion, the impact of such pairing, once learned, does not diminish with time. The association must be actively unlearned.

Pairing, priors, and politics

Hopefully we’ve laid the groundwork clearly enough that you can see where this is going. But just in case the connections aren’t clear I’ll just say it. Politics and political propaganda are uniquely positioned to subvert these basic learning processes to harmful ends.

Let’s analyze a common scenario with an eye towards the types of learning processes we’ve discussed.

A politician gets up in front of the press to give a statement. Since we were children we’ve associated the government with authority, integrity, honesty, and having a legitimate concern for citizens. All of these associations, whether we’ve come to question them or not, are automatically evoked. This means that without even being aware of it our prior expectation is that we will be receiving accurate, unbiased information.

The official makes a statement about the economy. Times are tough and we’ve had to make some tough decisions but the deficit was too large and we’ve had to cut back because having a deficit is not responsible and we’ve got to be responsible like a household.

Ever since we were children we’ve been told that saving money is good and spending money you don’t have is bad. People who aren’t responsible end up in collections or declaring bankruptcy. People work hard and make sacrifices to get out of debt.

All of these learned associations prime us to accept the official’s account.

Later we read a news story that says that actually the budget cuts went towards tax cuts for landlords and the wealthy and will not help the average worker at all. We begin to question the narrative of deficit reduction. We become somewhat skeptical.

The official fronts the press again to set the record straight. Despite our newfound skepticism once the official stands up all of the formerly-learned associations about government honesty and integrity are evoked, resetting our prior in favor of the narrative.

The government official says that there have been some lies in the press about how their tax cuts were meant to benefit the wealthy. This is untrue and a lie spread by the radical left, who hate our freedoms and want to destroy our country and set up a socialist society. The goal of the tax cuts was to incentivize investment because anyone knows that increased business prosperity means increased prosperity for everyone.

This new speech evokes many positive associations between freedom, prosperity, and business and many negative associations between socialism, radicalism, and anarchy and disorder.

The media amplifies the speech for a news cycle. The facts of the tax cuts are drowned out by rightwing talking points and economists’ TV and radio spots about how we can’t have too much debt and how inflation is bad and the only way to get rid of it is to cut government spending.

The official fronts another press conference. Your prior resets…

Unlearning and relearning political reality

You can see how so many things around how our social and political systems function are geared towards hijacking these learning processes for the benefit of a narrative that prioritizes the capitalist status quo. Because of this long history of associations we must fight hard if our learning process is to lead us to an accurate understanding of our economic and political reality. There are a few things that can help.

First, we should think critically about our own opinions. Many of our opinions aren’t based on facts but rather learned associations. Government spending is bad. Immigrants take away jobs. Taxes are just the government stealing our money. People on welfare are lazy. These associations are stronger than facts as they have a long history of many pairings but they can give way to facts if repeatedly confronted.

Second, stay away from the rapid news cycle. Try to read news critically and with an eye towards the long term trends and movements. Stay away from soundbites and read longer form content and analysis. Because of the delays between government policy and economic and social outcomes it’s difficult to determine contingency and causality from correlation. Unfortunately the media cycle, social media, and politicians are all too happy to fill in the gaps with misinformation or propaganda. We are at a disadvantage here because these groups have honed their message in such a way that it evokes deeply-rooted associations and it takes real effort to quash these knee-jerk reactions.

Third, and this I think is the most important, read books. Read books about politics and economics and history. But stay away from idealist portrayals written by the so-called “great men” or leaders of history or those scholars who seek to lionize these people or idealize history. Read books that try to capture the economic and material conditions that have accompanied social and political shifts. Read sources that capture the conditions and opinions of the majority of society, rather than the wealthy and powerful minority. This is sometimes known as “history from below”.

Read Marxist writers who analyze the material and economic conditions under capitalism so you can understand and demystify capitalism’s mystery for yourself and those around you. These types of books and essays reveal material and economic patterns that lead to characteristic political ideologies and movements, patterns that are at play today as much as at any time in history. The capitalist playbook doesn’t really change and recognizing its pillars–austerity, deregulation, privatization–and the way they are euphemistically framed is crucial to understanding and fighting the agendas of rightwing governments.

Our learning processes have served us throughout our evolutionary history, but in the political arena, they are often hijacked in ways that do not serve us, and certainly do not serve the greater societal good. It takes a conscientious, continual effort to understand the real causes and outcomes of our social and economic conditions. The learning mechanisms and processes are only as good as the information that goes in. A biased prior will lead to a biased view of reality. Garbage in, garbage out. The fundamental learning mechanisms won’t change. Hopefully understanding them can help us leverage learning towards a political movement that helps all in society flourish.

Great write up, Ryan. Associative learning explains a lot, in addition to your points about authority it trains us to avoid radical thinking. From famous cases of repression and assassination to simple social ostracization, and of course the demonization of socialism, the mind associates being too “extreme” with danger.

Thanks for your work here.

Reason dies alone, and this is why critical education paired with nourishing trusted social relationships is central to any transformative change.